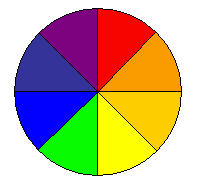

Focus Here

Achieve This

EXERCISE

FITNESS

NUTRITION

ENERGY

WEIGHT

SELF-CONFIDENCE

STRESS MGMT

FLEXIBILITY

RECREATION

CREATIVITY

REST/SLEEP

MENTAL CLARITY

RELATIONSHIPS

FULFILLMENT

SURROUNDINGS

ORGANIZED

Health and Wellness Coaching

Change your mind to change your life.

Fake Nostalgia for a Pre-Therapy Past

By Erik Kolbell. Published in the New York Times.

Link to the original newspaper article.

Old Gus sat on his customary bar stool in the corner, tossing down the bourbon and tossing out the barbs.

"I can tell you one thing," he announced, as I recall. "Back in my day, you didn't have young kids going around talking to shrinks, yakking about their fee-ee-ee-lings, getting all doped up on medications.

"Back in my day, kids were kids! We worked out our problems on our own. We didn't go crying to some stranger with a whole bunch of initials after his name."

Gus was ridiculing a conversation a fellow therapist and I were having about a 13-year-old she was treating for depression and acute anxiety. I didn't rise to his bait, but it wasn't because I had no interest in defending my profession. Rather, as with the college guys at the other end of the bar lamenting yet another epic collapse by their beloved Jets (this was before the team got good), it was that I'd heard the complaint so often it had become tiresome.

Not that Gus was entirely wrong. A greater percentage of young Americans than ever receive treatment - talk therapy, medication or both - for psychological disorders, and the number is steadily rising.

But when I think about what life was like in my day (I'm in my mid-50s, and Gus is probably 20 years older), I'm not so sure this is a bad trend.

One of my most vivid and least cheerful childhood memories is how discouraged I felt when it dawned on me that most of my peers could sit down for an hour or so at a time and plow through homework assignments without fidgeting, getting out of their chairs, pacing the floor or succumbing to the distractions of their rooms.

Nor was environment the determining factor; I found it difficult to sit still and concentrate in the classroom, glued to my desk, with an assignment right in front of me and the teacher hovering over me. It was never a matter of resenting the work or not knowing how to do it. To my reckoning, it was just physically impossible to be still and focus on a task for more than a few minutes at a time.

With this as a part of my past, the first time I read the criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder - "often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork ... fails to finish schoolwork, chores or duties" and so on - my only surprise was that they didn't include "Prefers G.I. Joe or flipping through baseball cards to civics lessons and pop quizzes."

In short, I was an A.D.H.D. kid, lacking only a diagnosis. And now that I know that the condition was a result of my body's inherent inability to manage the flow of neurotransmitting chemicals like dopamine and serotonin, all of my parents' heated entreaties to "buckle down" and "pay attention to what's in front of you" were about as useful as telling a nearsighted child to see clearly without glasses.

As I grew into adulthood, I was left with a string of unanswerable but concentric questions: Could medication have helped me to concentrate on my schoolwork? If so, would I then have been a more industrious student? And if I had been a more industrious student, could I have developed more of a passion for reading and for learning? And if I had developed that passion, would I be a happier, better, more productive human being? If, and if, and if ... I'll never know.

And while my own life is dogged by the possibility of unfulfilled possibility - what might have been had I been treated - what really haunts me is the memory of full-blown tragedy in the lives of some of my childhood friends.

I think of a pretty but perpetually sullen girl named Maureen, her body scarred for life by an abusive mother who (as Gus would say) was not above giving her daughter what for. Or a tall, lanky guy named Dave, a star athlete with Hollywood looks who stunned us all by putting a gun to his head and taking his life.

To their horrific stories, I could add the countless quotidian ones of seemingly normal, everyday kids who endured overbearing siblings or bullying classmates, who didn't get included in the secret, invited to the prom or chosen for the volleyball team, whose father one morning just up and left the family because he got a better offer from another woman. Those who just couldn't work out their problems on their own (Gus again). Who knows how much more bearable their lives might have been if they had received the proper intervention?

It was only much later in life that I began to appreciate the many insidious ways in which psychological well-being can be altered by things outside a child's command.

Most children exercise very little power over the decisions that affect their lives. They don't decide who their parents are, where their family will live, where they will attend school, when they will reach puberty, who will or will not befriend them. They have limited control over their athletic skills, their looks, their wit, or whether, in the great Serengeti that is their schoolyard, they will be predator or prey. They are as much the subject of their story as its author.

At toxic moments, the insights to be gained from a professional who takes this stuff seriously (and in some instances the medications that can bring calm to chaos) are eminently useful to the child who is looking for a narrow path through some very difficult years.

Erik Kolbell, a psychotherapist in New York, is the author of a book of essays, "The God of Second Chances."

Use your Back button to return to the Excellent Articles page.

Disclaimer: As a Health Coach, I will never attempt to diagnose, treat, make claims, prevent or cure any disease or condition. I advise my clients that Health Coaching is not intended to substitute for the advice, treatment and/or diagnosis of a qualified licensed health care professional.